1600s

Boston’s story begins in 1630 when English Puritans, led by John Winthrop, established the settlement as part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Seeking religious freedom and economic opportunity, they named the town after Boston in Lincolnshire, England. The initial settlement was on the Shawmut Peninsula, a small, marshy area surrounded by the Charles River and Boston Harbor. The population grew modestly, reaching about 1,000 by the end of the decade. Early expansion was limited by geography—tidal flats and hills constrained growth—but the settlers built a tight-knit community centered around a meetinghouse and common land (now Boston Common). By the century’s end, Boston had become a hub for trade and fishing, with a population nearing 7,000, though it remained a compact colonial outpost.

1700s

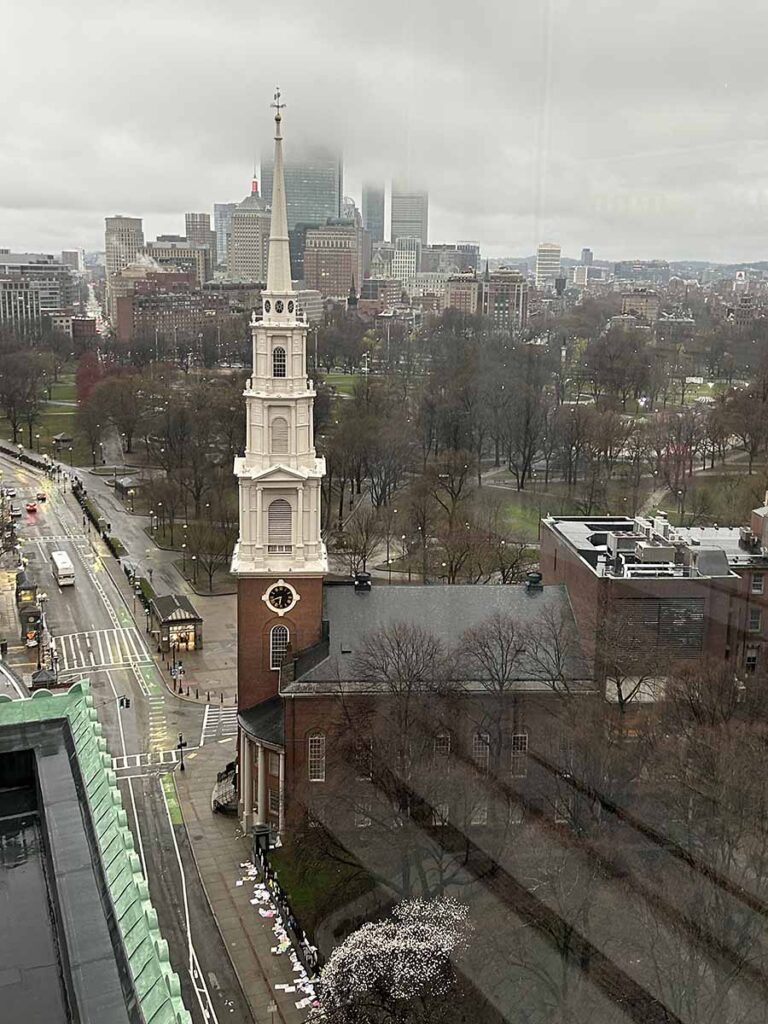

The 18th century saw Boston transform into a bustling colonial port. By 1700, its population was around 7,000, swelling to over 15,000 by mid-century. Trade with Europe and the Caribbean fueled growth, with shipbuilding and commerce driving the economy. The city expanded beyond the peninsula, reclaiming land from marshes and wharves. Key events, like the Boston Massacre (1770) and Boston Tea Party (1773), cemented its role in the American Revolution. Post-independence, Boston rebuilt and grew, reaching about 25,000 by 1800. Neighborhoods like the North End and South End began to take shape, though much of the city still hugged the waterfront. Fires and disease occasionally hampered progress, but Boston emerged as a political and cultural center.

1800s

The 19th century marked Boston’s rapid expansion and industrialization. The population soared from 25,000 in 1800 to over 560,000 by 1900. Massive land reclamation projects reshaped the city—areas like the Back Bay and South Boston were created by filling in tidal flats with earth from flattened hills. Irish immigration, especially during the 1840s famine, swelled the workforce and diversified the culture. Railroads and factories spurred economic growth, while institutions like Harvard (nearby in Cambridge) and the Boston Public Library (founded 1852) boosted its intellectual reputation. By century’s end, streetcars connected sprawling suburbs like Roxbury and Dorchester, absorbed into the city through annexation, making Boston a true metropolis.

1900s

Boston matured in the 20th century, balancing growth with preservation. The population peaked at nearly 801,000 in 1950 before suburbanization trimmed it to about 589,000 by 2000. Early decades saw infrastructure booms: the subway system (America’s first, opened 1897) expanded, and highways like the Central Artery (1950s) reshaped mobility—though often at the cost of neighborhoods. The Great Depression hit hard, but post-World War II recovery brought urban renewal, including the Prudential Center (1960s). Tech and education became economic pillars, with MIT and Boston University thriving. By the late 1900s, gentrification revitalized areas like the South End, while the Big Dig (begun 1991) aimed to untangle downtown traffic, setting the stage for future growth.

2000s

In the 21st century, Boston has solidified its status as a modern, innovative city. The population rebounded from 589,000 in 2000 to over 675,000 by 2025, driven by a tech boom, biotech hubs like Kendall Square, and a robust university presence. The Big Dig completed in 2007 transformed the waterfront, replacing an elevated highway with green space and spurring development in the Seaport District. Housing demand soared, pushing expansion into former industrial zones and suburbs. Sustainability efforts, like bike lanes and green buildings, reflect contemporary priorities. Today, Boston blends its historic core—think Freedom Trail landmarks—with a forward-looking skyline, maintaining its identity while adapting to global trends.