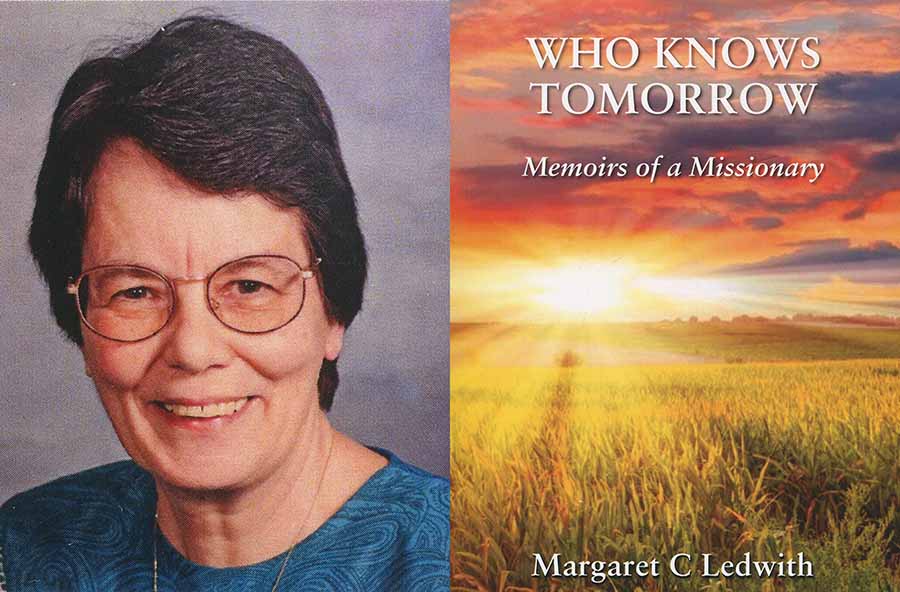

Who Knows Tomorrow by Margaret Ledwith is an account by an Irish missionary of her career. It gives a glimpse into the dangers faced by irish missionaries in conflicts abroad and an account of a pollution in fear in the face of conflict.

Who Knows Tomorrow by Margaret Ledwith offers insight into the life of Granard born missionary Margaret Ledwith, detailing her experiences and the risks faced by missionaries operating in conflict areas, particularly during the Biafran Civil War and her experience at Emekuku Hospital

Sr Ledwith details her return to a hospital filled with critically ill patients amid air raids on November 1, 1969. Hospital staff worked through fear as they performed surgeries under dangerous conditions, with patients and staff seeking shelter from MiG jets overhead.

The memoir illustrates the dire situation in Biafra during the conflict, including the extensive loss of life—over two million people. The account captures instances of resource shortages, the creativity of the staff to provide meals, and the critical humanitarian efforts taking place amid warfare, including the evacuation of patients for safety.

The text recounts personal tragedies, including the loss of Sister Cecilia Thackberry, and highlights the role of various religious and humanitarian organizations during this tumultuous period. Sr Ledwith conveys the emotional weight of witnessing suffering and the challenges posed by ongoing military operations, creating a vivid portrayal of survival and resilience during a harrowing period in history.

1969: Air raids and shrapnel

On 1st November 1969, I started work again in the hospital. Everything was different, and I saw for myself that the hospital was filled with very ill patients. When I met the staff, they welcomed me back. They said they were living and working in fear. Nevertheless, they continued to keep the hospital going under very difficult conditions. Surgeries were performed almost round the clock. The nurses were admirable, doing their best to care for the patients, trying to shield them when Federal MiG jets flew overhead. During that time everyone looked for shelter. The patients who were mobile jumped under the beds, and all of us sought safety somewhere.

During the air attacks we made a beeline for safety under the stairs in our house, so as to escape the flying and burning shrapnel. Food was in short supply all round, for everybody, as were most medicines and hospital supplies. Sr Ursula was creative and produced meals for us. Red Cross flags were flying over the hospital and houses in the compound; we hoped that would give us protection. Other buildings outside the hospital compound in the area had Red Cross flags flying as well, but these were often disregarded. It was a miracle that the hospital compound was never strafed. One day in the midst of such tragedy, we had an army wedding. Sr Bridie and I were outside the chapel to wish the couple well. It was impossible to find a wedding ring in the circumstances. Instead, they improvised by using a ring from the top of a Coca-Cola can for the occasion.

Each day we tuned into the BBC World Service as it kept us up to date with the political situation. The war continued. It became clearer by the day that the Federal troops were gaining ground and pushing back the Biafran army. Fierce fighting continued in November and December, with many lives lost, while others were badly wounded. People were extremely fearful, and rightly so, as the MiG jets passed over their area and usually left a wave of destruction. Homes and villages with the people’s open markets were sometimes levelled to the ground. Again and again, they were bombed, and indeed in some places, there was almost nothing left to shelter the people. The bombing and strafing had gone on for at least three years, often killing and maiming untold numbers of people.

Most people travelled at night for fear of being hit by falling shrapnel. One afternoon prior to my arrival, two Presentation Sisters (PBVM), Srs Gertrude and Cecilia from the English Province of the Presentation Congregation, were travelling in their car with their driver near Owerri when they were strafed. The driver heard the MiG jet overhead, he stopped the car, and they all ran for shelter. Sadly, however, Sr Cecilia Thackberry was hit and killed. She was the only woman religious who lost her life in the Biafran war, as far as I know. She was taken to Emekuku Hospital but pronounced dead on arrival. May she Rest in Peace. Her funeral Mass was celebrated in the parish church in Emekuku. Then she was buried in the grounds of the church. It was sad news for Sr Cecilia’s family, for her companion Sr Gertrude, the sisters in her Congregation, the local people, priests, sisters and missionaries.

The Federal troops are on their way

As the war continued, the Federal ground troops were advancing and taking over vast areas. It was claimed that overtwo million people, including children, died during the dreadful Civil War. It was difficult to see the people suffering, and in many ways we were unable to respond to all their needs. We provided for as many as we could with some food and medical attention. This offered temporary but necessary relief. It was a pathetic scene. Plans were made to take some of the children, who suffered from kwashiorkor which is a severe form of malnutrition, out of Biafra to Sao Tome. This special care planned for them, gave some hope for their survival and indeed many did survive as a result. Parents gathered as the children were checked and counted. It was heart breaking for the parents to part with their children. The wailing continued as the transport drove them away. Parents were sad, but the promise of treatment and food offered the children some quality of life and, in some cases, life itself. Parents gave the permission for their temporary care but they were not allowed to accompany them, which was very difficult for both the children and the parents. Holy Rosary Sisters were among others who went and took care of those children in Sao Tome and Gabon.

There was starvation all over Biafra. In those days, it was possible for us to visit the clinics in the villages very early in the morning. Those visits made us more aware of the plight of the people. They were dependent on the food received at the feeding centres, and the medical care which they got in the clinics, to keep them alive. During each distribution, they lined up and waited for their rations. You can imagine this sight, with thousands waiting in line for food. The local people helped to keep order and usually did a great job. The Holy Ghost Congregation, through its members, successfully managed the massive relief operation, distributing food, medication and other necessities of life during the war in Biafra. Frs Jack Finucane CSSp and Fintan Kilbride CSSp were among the many missionaries who were integral to the planning and supply logistics required for supplying the various centres and clinics.

Our vans were filled each night with whatever food and medicines we had, all of which were provided by Caritas lnternationalis. We kept in mind the special needs of the children as best we could. One of the outstanding people who helped with this work was Anthony Obinna, who is now the Archbishop of Owerri Diocese. He was a seminarian when I met him in the hospital in those days during the war. Around Christmas 1969, there was less fighting and bombing. With the coming of the New Year it all started again. Even though there were rumours of a ceasefire, there was not much evidence of it.

A question was raised in church circles concerning the morality of the continuation of the war and as time went on this was a new concern to reflect on. Only for the churches’ intervention and the NGOs’ and the local people organising of feeding centres and medical supplies, there would have been a higher number of casualties. The international journalists who came to the war torn areas and saw the scene for themselves raised awareness worldwide of the plight of the people in Biafra. As a result, international generosity continued to support the people, thus helping to prevent more starvation and infection, especially among women and children.

One day it became clear to us that the Federal troops were nearing Owerri. French Red Cross personnel suddenly appeared and came to stay in our house with us. Given that the troops were only a short distance away from the hospital, it was important to protect the patients and take them to a safer place. After discussions with the Red Cross personnel, we were told that the staff and the patients had to be moved soon to Amaimo, a village further into the countryside. The next day before daybreak, members of the Red Cross started to evacuate the hospital patients for their safety, as they had done a few times before during the war.

When some of the patients who had injuries heard what was about to happen, they took off from the wards themselves on their hands and knees. They made their way out of the compound and into the countryside. No way did they want to be moved by members of the Red Cross to a new location. Amaimo was a place which was set up during the war when danger warnings were given, and safety for patients and staff was essential. Most of the patients were taken there that day from Emekuku Hospital. It was such a sad scene to watch all of this happen. After the evacuation, the hospital compound looked like a ghost village. The only people left were the sisters in our house and the cook until the Red Cross staff returned after transferring the patients.

That afternoon, as we were gathered for a meeting in the front parlour of our house, a car drove up the avenue. We saw it coming and when we opened the door we saw Mother Magdalen Brady, MSHR (acting Regional Superior) and Fr Michael Frawley, CSSp (Regional Superior) coming towards us. We were pleased to see them, hoping to get news regarding the other missionaries who had been taken by the army. Moreover, we then had special cheese to share with them, kindly given to us by the Red Cross personnel when they moved into our house. This was such a treat at the time. Little did we know that our visitors came with sad news. They found the sisters and priests in prison in Port Harcourt. They had been taken by the army the previous day and placed in prison. We were stunned. While all of us were silent, Fr Frawley broke into song and with his beautiful voice he sang his favourite song, ‘Liverpool Lou’, written by Dominic Behan. It certainly broke the silence. Then we chatted for a while before they left us. They were going to visit other missionaries on their way back and give them the latest news from their travels.

God will protect you.

In many ways it began to dawn on us that our days were numbered in the country. We had no idea what tomorrow would bring. An Igbo saying came to mind, ‘Onye ma echi’, (Who knows tomorrow). This saying, written on many of the Igbo trucks, caught my eye during my first missionary experience in Makurdi, Benue State, Northern Nigeria. I never forgot it. Don’t you think it is an appropriate title for my book?

The days went by, and we were very busy in the theatre as patients continued to come in for emergency treatment. Shortly after surgery, the relatives would take the patient to their home as it was safer to do so. We were on alert, as we could be ordered to leave our compound at short notice. We were advised to carry our passports on our person, giving us some security in case we had to leave the country at short notice. One morning, while on duty Sr Bridie told Sr Mona and myself that her passport was in her suitcase in Amaimo.

Silence immediately followed, but action had to be taken fast. Amaimo was quite a distance from where we lived. I decided to accompany Sr Bridie to collect her passport. We went back to the house where Sr Ursula Parks arranged for the driver to take Sr Bridie and myself in the community car. It was dangerous to travel as we could be strafed from the air in daylight, but there was no option as Sr Bridie needed her passport. The driver had a pass, which he produced at the blockades. Only once were we asked to step out and remove ‘our bonnets and boots’. There was not much delay, and the soldiers waved us on which was a help.

The roads were empty and we travelled fast. Gratefully, we got to our destination without too much hassle. On entering the compound in Amaimo we saw Mother Magdalen at a distance. We knew she would be far from happy to see us travelling, especially in mid-morning. Thankfully, Sr Bridie armed with the passport returned to the car; and we set out on our return journey without delay. We were well on our way home when all of a sudden the car stopped on the road. It would not start again.

The cars were mostly old and worn out with little or no repairs carried out during the long war. There we were in the middle of nowhere under the tropical sun, with no one to turn to, and no other car in sight. We waited and waited and prayed for transport, when out of the blue, we saw a car coming towards us. It was Mother Magdalen, Sr Maura Byrne, and their driver, hoping they could make the journey safely to li1iala. Their car was full to the brim. There was nothing else to do but pack in on top of the loads. We said goodbye to our driver, left him with the broken down car, and off we went at speed. They dropped us outside the front door of our house in Emekuku and set off down the avenue in a hurry on their journey. They only just got out the front gate when we saw the Federal armoured trucks turning in from a different direction, and coming up the avenue nearing the front door. We knew then we were in trouble and we made sure we could not be seen at the window.

We went into hiding and the cook shouted in our back window, ‘God will protect you, I have to go.’ How grateful wewere to have made it home just minutes before the ground troops appeared. We were very relieved that we got in the door safely, and also that the sisters and their driver got out of sight with only a few minutes to spare. While we were away, Fr James Mohan CSSp, our parish priest, had come to our house to be with us. He was inside with the sisters when we arrived. They were so relieved to see us off the road and back home safely. We remained quietly in hiding. The soldiers did not get out of their Saladin armoured cars. They just viewed the front of the house and saw that they had to take another route to reach the hospital. They had no idea that there was anyone in our house.

After some minutes the Federal troops reversed their trucks, drove down the avenue, and turned onto the main road. A little further on they entered the hospital compound. They remained there all throughout the afternoon, and into the night, while many more troops joined them. From our house we could hear loud music and their celebrations. At around midnight we could hear footsteps as a few soldiers walked around the house, but thankfully we were in darkness. Sr Ursula had gone to bed for a rest while Srs Mona, Bridie and myself tried to listen. There was a room at the rear of the house which had no windows, in which we sat silently, nodding off occasionally. Fr Mohan went to bed earlier and, at one point we heard him snoring. Our anxiety was raised for fear that the soldiers might hear him. I went into his room and woke him up. He hardly knew where he was.

‘God do not kill us.’

The morning of 14th January 1970 came and the soldiers started to surround the house, and came to our back window. We surfaced from our hiding spot. When they saw us inside we could immediately see the amazement on their faces.

They drew their rifles and moved to the front windows and front door of the house. Sr Mona, a brave soul, opened the door and we all marched out after her. Fr Mohan came with us and we kept walking out with our hands up. These tall soldiers, who we later learned were from Chad, lined us up in front of the house with their rifles pointed at us. I shouted, ‘God do not kill us.’ Sr Bridie leaned down to help Sr Mona as she seemed to be fainting. She was unsteady on her feet, almost falling to the ground. One of the soldiers noticed the movement and hit Sr Bridie on the shoulder with his gun. While all this was going on, an armoured car drove up to our front door. An official, who was wearing a red beret, got out. The soldiers saluted him so we knew he was important, and he said ‘Halt, Halt’. As he came toward us, we were terrified. He stood in silence, looked at us and said, ‘Take some water with you and get into the cars which are in front of the house.’ We went back into the house and took some bottles of water from the fridge. We also took our little prepared exit bags containing our passports. We got into the cars and we were taken by the soldiers to an unknown destination. The war was still on and the Federal MiG jets were in the skies.

Later, while driving on the road to Port Harcourt, the drivers of the cars were directed to a small soldiers’ camp on the Owerri roadside. There we were allowed out of the cars and both the gentle breeze and fresh air were welcome. The army captain spoke to Fr Mohan, after which the captain and some of his companions took off leaving the soldiers to guard us.

In the afternoon one of the soldiers came over to talk to us. He had tins of condensed milk in his hand and gave us one each. He knew that we had nothing to eat or drink for a long time, and he kindly wanted to share with us. He even opened the tin with a bullet, making two holes so that we could drink directly from the tin. We appreciated his thoughtfulness. To drink water was not an option, as rumour had it that the water was poisoned. When all was quiet in the soldiers’ camp, Fr Mohan spoke about the morning miracle and how it came about. As it happened, the captain who gave the orders to us at the house that morning had been one of Fr Mohan’s seminarians, and father recognised him. That was a revelation to us. Indeed we had felt, and knew somehow, that we were saved by him. He was a native of the River State area. He had left the seminary when the war started and joined the Federal –Army. How grateful we were, and we all thanked God for His Providential care of us. Surely Bishop Shanahan was looking after his daughters and brother.

Later that day the captain returned. Fr Mohan told him that he had left his passport in the parish house in Emekuku and requested permission to return and get it. He got the permission and Srs Ursula and Bridie accompanied him in the car driven by one of the soldiers. Sr Mona and I were left behind. We made our way to sit in one of the broken down cars in the army camp. At least we would be out of sight and safer, since we were very visible, all dressed up in our white habits.

The travellers were away a long time, because their driver delayed to making the return journey until after dark. We were really glad to see them when they eventually arrived back. It was a pleasant surprise for them to see that we were safe and they shared with us what they observed as they journeyed along. The roads were clear as people were afraid to venture out. They had gone to our house in Emekuku to find that nearly everything in it was gone. The wards in the hospital were empty, nothing was left in them either. It was an upsetting scene to observe, even the water in the fridge was missing. The priest’s house was not touched, so fortunately Fr Mohan got his passport there as that was really important to him. That night we remained where we were at the camp. We were feeling quite ill from drinking the creamy thick milk but at least it kept us hydrated. Morning came but there was no sign of us moving.

1970: Arrest and Trial.

In the afternoon of the following day 15th January 1970, the captain returned and he told us the war was over. The Biafran Lieutenant Colonel, Odumegwu Ojukwu, had made a broadcast in the morning, stating this fact. The captain made a request for medical help from us because there was a very serious problem. He told us that a truck full of soldiers had an accident near the entrance to Emekuku Hospital. Some soldiers were dead, while others were severely injured. He asked us to return to the hospital and open it to care for the wounded. We had a conversation with him and he pleaded with us to take care of the situation. Aware of the tragedy, we were prepared to help out in the emergency but we wanted to be assured that all soldiers of different ethnic groups would be cared for equally.

The question facing us then was how could we start up patient care in the hospital, knowing that all of the contents had been removed after we were taken away. There were no patients’ beds left, not to mention the lack of medications and food. He gave us an assurance that everyone had permission to receive treatment. He also said that he would arrange for medicines, intravenous fluids, food and bed linen to be delivered by helicopter that evening. After considering the situation, we decided to go back to the hospital and were taken there by the soldiers in cars.

We were again back in the hospital. Our emotions were mixed, of course, glad to be on familiar ground once more, but anxious about how we could manage the situation. We were even more concerned when we arrived in the house. Hardly anything was left. We looked around, and then I remembered that there was one locked cupboard upstairs. We got the key and opened it and then found a number of mattresses and blankets. So that was a blessing and a consolation. We also found the money we had ‘banked’ prior to our departure, bidden in the centre of Our Lady’s statue which was situated on the ground floor. What a secure banking system we had! Our Lady had taken good care of it!

Soon the ‘bush telegraph’ worked and the people started to appear to welcome us back. We lost little time going to the hospital, and there we found the injured soldiers lying on the floor in one of the wards. There was little medically or surgically that we could do. At least we were able to communicate with the conscious soldiers and reassure them that relief was on the way. As time went by some of our hospital beds were returned. The local people generously came and helped us to set up the wards again.

Late in the evening supplies came; they were essential, and a godsend for all. We now had some basics for the care of the ill and wounded. Also, we got food and drink to share with the soldiers and other patients. Many of the latter, who were previously wounded, had hidden in the countryside. They had crawled back to the hospital when they felt it was safe to do so. We ourselves got food and drink which was very much appreciated.

Fortunately, we had kept ourselves healthy, which was essential and at least we had the energy to care for patients. As the days passed, more and more patients came to the hospital. Members of the French Red Cross appeared again andmoved into the house with us. They brought all sorts of medical supplies and food which they generously shared. Many of the very ill patients were treated and saved with their intervention. Being professionals, they were a tremendous support to us in the hospital. It was a joy for us when the Immaculate Heart of Mary Sisters (IHM) joined the team. Their presence meant a lot to the staff and the patients. They brought their own expertise; later they would administer the hospital.

Two weeks later, early one fine morning, army officials arrived and told us to leave the hospital and report at theGovernment District Office in Owerri. We were now preparing for our exodus once again. Each of us gathered a few worldly belongings and a bottle of water. We readied ourselves to leave, said our goodbyes, and made sure we had our passports.

The news of our departure started to leak out to the staff, who looked so sad. We could see them peeping from different vantage points as gradually they began to realise that something was happening. They saw the Federal Army Commander and other officials at the front of our house, which was not an everyday occurrence. As I exited the front door, out of the corner of my eye I saw Anthony Obinna. He had been a constant support to us while caring for the people. I was given permission to say goodbye to him. It was then that I gave him keys I had in my hand. Years later, as Archbishop of Owerri, he still remembers that incident and claims to this day that I gave him the keys of Owerri Diocese.

Detention in Scooby Doo nightclub

Uppermost in our minds was the question, ‘What is going to be the next move for us?’ There was an eerie silence, all around until suddenly the soldiers came closer and told us to get into the cars. We were taken a short distance away to an old building that was used years before as a night club, known as ‘Scooby Doo’, or so we heard. Those who were familiar with the Port Harcourt road knew of this building and its use.

We were guided into the building. The women were told to take the top floor while the men were put on the ground floor. There were very few amenities that we could see. We found iron beds with no mattresses, but only screen bottoms on the beds, and no bed linen was to be seen. If my memory serves me correctly there were no curtains on the windows. At least we could lie down and rest as we were exhausted, having been exposed all day to the tropical heat. The soldiers stayed on guard around our building. We continued to feel anxious, not knowing what our future was shaping up to be. Fortunately, each day the soldiers brought us food and drink, which we heard had been ordered from the hotel. We were indeed grateful for it and it kept us alive.

On the whole, the women managed to stay physically well, while some of the men got quite ill. Sr Mona was asked by the. officer-in-charge of us to visit the ill priests as he was concerned about their health. She did this and was able to order medication for them. A few of them were very ill, and she pleaded with the officer to request a bed at the hotel for them for a day or so. The request was given a favourable reply. Those who needed further attention were transferred to the hotel to rest.

One morning, while out walking, my curiosity was aroused when I spotted something strange in a soldier’s hand. Sr Bridie was with me when I dared to ask him what he was holding. He looked up at me and said, ‘It is a hand grenade.’ We took many steps backwards as he went on to explain how to use it. You could not believe how scarce we made ourselves. We were really scared and ran. He smiled and got a kick out of our dismay. As the days went by, we had to take care of our clothes and wash them for one another as we had no extra ones to wear. There were no washing machines, and we had to make do with our short supply of personal soap for washing. The sunny climate favoured drying and so was much superior to a clothes drying machine. It was helpful that our laundry dried quickly.

In the early morning of each day, with permission, we made a large circle in front of our building. Mass was celebrated out in the open air with the singing birds accompanying us. The soldiers ringed us but kept at a distance. It was a privilege to have the freedom to gather outside in the open air and to share the Eucharist.

Pilots and our plight

It came to the notice of the mercenary pilots who had been employed by the Federal Government, and other officials staying at the Intercontinental Hotel, that we were in a detention camp not far away. They decided to approach the manager and the army officer to ask if they could invite our group to come to the hotel for a meal. What a generous and thoughtful gesture by the pilots to finance the meal and thankfully, they got the necessary permissions. Not only that, but they offered to vacate their rooms for the night so that we could enjoy a break. Even the hope of the treat lifted our spirits.

One evening, the officer came to ask the soldiers to bring us to the hotel and so they did. It was like a fairy tale, but it was our reality at the time. When we entered the hotel, the pilots came to greet us. They were from many different nations and cultures. How surprised they were to see that we missionaries had remained with the suffering people in Biafra. They had no idea of this during the bombing raids. When the war ended, a number of the pilots decided to come together to share experiences, and to relax at the Intercontinental Hotel. That night, we only met them briefly on entry to the hotel. After that, they were kept apart and we were guarded. Bishop Joseph Whelan thanked them on our behalf for their kindness and thoughtfulness. We enjoyed that meal together, the air conditioning and the relaxing atmosphere.

As we were enjoying the meal Fr Frank Mullen CM appeared at our table. Earlier, he had been taken captive but somehow got permission to visit us in the hotel. He needed to see Bishop Whelan, to hand over the keys of a number of the priests’ cars. Later, Archbishop Francis Arinze, Archdiocese of Onitsha, came to greet us and to collect the car keys. It was late when we decided to retire and move toward our ‘ensuite’ rooms. What a delight it was to get into a bed and sleep beneath cosy white clean sheets. We appreciated that luxury for one night. Our rooms were guarded by the soldiers, who woke us the next morning.

After breakfast we were rounded up and taken back to our detention building. Sr Laboure, lived in Port Harcourt and knew the area. When she got the chance she took off on foot secretly to visit her house, as it was only a short distance away. The soldiers never missed her but we grew anxious about her whereabouts. We hoped that she would soon return, and eventually she did. How glad we were to see her and hear her story. She had walked to where she had lived in Port Harcourt. With a heavy heart she said her goodbyes to her home and the few local neighbours she met. They were astonished when she told them that we were in detention. After the long walk, she was physically exhausted and her ankles were visibly swollen.

Ann Boleyn goes on trial

The officer informed us a few days later that we were to have a trial at the court house and that we would be taken there. In detention with us was a priest, Fr Redmond Walsh CSSp, who, being a canon lawyer, tutored us to say very little when charged in court and to deny the charges brought against us. The charges were, that we had been illegally in the country and remained, despite not having permission to be there. The day arrived, and we were all taken to the court house in Port Harcourt by the soldiers. It was an anxious time as we were living with the unknown. We stood around until we were called to the front of the hall, one by one in alphabetical order by our surnames, as recorded on our passports. Sr Dorothea Boland (Ann Boland) was first to be called, as she was at the top of the judge’s list. The judge shouted out her name calling her ‘Ann Boleyn’. As he said this, we erupted into laughter. All of us were as tense as could be whilst awaiting our call. It was almost impossible to stop the laughter and the noise. The judge kept on saying ‘SI…LENCE SILENCE in the court.’ Eventually the scene was brought under control. Then Sr Dorothea braved her way to the front of the court. She was asked to swear on the Bible, which she did and all of us followed the same pattern.

The court proceedings continued, and one by one we were each fined one hundred pounds. Fr Paschal Kearney CSSp was the one exception to this. It may have been because he was from the six counties and he held a British passport. Fr Redmond was one of the last to be called up. The judge asked him was he married and he said, ‘Yes, but my wife died.’ The judge continued to question him and asked him what she died from. He quickly responded and said, ‘She died of thirst!’ There was again another outburst of laughter. .At this stage we were worn out and were relieved when the judge gave us permission to leave. It was only later on that we heard that some of the priests in our midst had ministered in the Port Harcourt Diocese and knew the judge. Soon we were on our way back to our detention building to wait until the money came from Rome to pay our fine. It took a few days for the transaction to come through. Around this time, some of the Irish newspapers ran an article with photographs of us in detention. It was very upsetting for our families when they read this. Up to this point they had no idea that we had been held in detention by the Federal Army. Fortunately, we were not aware at the time that the papers carried this news.

Back in prison

When the fines were paid, we were informed of the plan for us; we would be taken from our detention camp to Port Harcourt Airport to exit the country. Instead we were driven to an entrance gate leading to Port Harcourt Prison. There was rebellion in our group when we were ordered to enter the prison. Since our fines had been paid, we were of the mind that we should be allowed to leave the country. The soldiers surrounded us; they were far from happy with our behaviour. Some of us gathered sticks and lit a bonfire outside the prison gate. Sr Thomas entertained us and danced a jig, to the amusement of all, especially the soldiers. They laughed when they saw the lady, advanced in age, in her long white habit dancing around the fire. The rest of us broke into song and sang all of the rebel songs that we knew.

As evening approached, a senior officer came to finally tell us to move into the prison. Bishop Whelan CSSp told the officer that he would need to drag him in first. Then the bishop told us what was about to happen and said, ‘If I am dragged in, all of you should follow for fear there would be any confrontation or shooting’. The soldiers soon took hold of the bishop and brought him into the prison. There was no option then but to follow him. The priests were taken first. Later, when they got an area ready for us, we were shown into a fairly large room, with beds, but no mattresses or bed linen, and a convenience in the corner. There was a woman lying on the floor, chained to the ground. The wardens soon released her, took off her shackles and set her free. I was so upset to see her in such a state, but to this day I remember the joy on her face as she was led out, waving and bowing to us. It was her lucky day.

Trying to come to terms with what was happening, each of us just sat on our iron bed in silence for some time. Then we started to arrange the beds as best we could. The warden arrived looked at us and rook a count. She left us and soon returned’ to let us know that food and drink had come for us. Sr Louise Steen DC and Fr Rodney Crowley CM heard about our imprisonment and came to the prison with food. What a treat that was and the wardens kindly took it to us and the priests. In the late evening, our warden came with keys in hand and locked us in the room, which had no windows and little air. We lay on the bed screens and despite the heat some sisters still managed to sleep.

The next day we learned of one another’s plight and that some of us were exhausted with the lack of sleep. There was little any one of us could do but live in the hope that our prison experience would be short lived. The days were very long. We went out during the day and exercised a little in the enclosed garden, which we called the ‘hen run’. We were so fortunate to be gifted with food prepared for us by the sisters and priests. Our good angels arrived twice daily. On the second day we were informed that we were now permitted to have an early morning Mass. This permission was requested by Bishop Whelan. We were in our little garden while the priests gathered in their patch close by. We were grateful to have the opportunity to praise God together, also to thank Him for His care of us thus far, and to ask for future protection. During the Mass, Igbo prisoners climbed up the trees and sang the Mass hymns in Latin. It was such an emotional scene for them and us.

That day, Sr Bridie and I met the warden and dared to ask her_ if we could take our beds out on the veranda during the night. We were prepared to sleep outside and leave the door open so that the other sisters would have fresh air. She said that she would return with a decision. Permission was granted, so all of us felt happier and slept better having the cool air. During the night we were visited by numerous mosquitoes. We just put up with the inconvenience as there was no question of us getting nets for the beds. As the days went by we learned that our exit was delayed because of the celebration of Ramadan. This left us wondering how long more we were going to be detained.

Journey to Lagos

Thankfully, we did not have long to wait. After the weekend we were informed that we would be taken to the airport to leave for Lagos enroute to Ireland. The morning came and a big open-air army vehicle arrived as our transport. One by one we boarded the back of the truck. We left the prison with relief in our hearts. The soldiers drove us through the streets of Port Harcourt with the people lining the streets, looking at us with wonder on their faces. When we got to the airport our passports were collected and taken from us. They were not returned until we were in Lagos Airport heading for Rome. The soldiers took us through customs and directed us to the aircraft destined for Lagos. It was a relief to be more or less sure that we were on our way home this time. We had a good flight, arrived safely in Lagos and were immediately taken to a hotel.

The soldiers in charge then informed us that we were travelling to Ireland the following day. The hotel staff gave us ameal and our room number. We were grateful to rest for the night before our next long flight to Europe. The soldiers continued to guard us that night. The next morning after breakfast we were driven to Ikeja Airport in Lagos. It was 19thFebruary 1970. On arrival we were directed through customs and onto the aircraft. On the steps at the door entering the plane, we were given back our passports. As soon as everyone boarded the plane, we were on our way. Free at last!

- Margaret C Ledwith’s memoir ‘Who Knows Tomorrow’ is available online via Bruhenny Press https://gerrymurphy.com/publications/

- Also from the Missionaries of the Holy Rosary 48 Temple Road, Dartry Dublin 6. The cost is €20 per copy and proceeds from the sale of the book will support the work of the Missionary Sisters